(from "Letters from Ramanashamam"):

The devotee: “It is for that, is it not, that Bhagavan says that the best thing to do is to follow the path of Self-enquiry of ‘Who am I’?”

Bhagavan: “Yes; but in the Vasishtam it is mentioned that Vasishta told Rama that the path of Self-enquiry should not be shown to anyone who is not sufficiently qualified.

In some other books it has been stated that spiritual practices should be done for several births, or for at least twelve years under a Guru.

As people would be scared away if I said that spiritual practices had to be done for several births, I tell them, ‘You have liberation already within you; you have merely to rid yourselves of exterior things that have come upon you’.

Spiritual practices are for that alone. Even so, the Ancients have not said all this for nothing. If a person is told that he is the Godhead, Brahman itself, and that he is already liberated, he may not do any spiritual practices, thinking that he already has that which is required and does not want anything more. That is why these Vedantic matters should not be told to spiritually undeveloped people (anadhikaris); there is no other reason.” And Bhagavan smiled.

======

Vira Chandra: Neo-Advaita, as seen with modern teachers like Mooji, Papaji etc, often simplifies the teachings of Ramana Maharshi, sometimes bypassing the rigorous groundwork suggested by Ramana himself. While their approach makes these teachings accessible to a broader audience, it risks leading individuals to misunderstand or prematurely conclude they are fully realized without the necessary depth of practice and understanding.

Ramana Maharshi’s caution against revealing the ultimate truth to the unprepared is rooted in the understanding that such profound knowledge requires a certain maturity and readiness. Without it, there's a danger of complacency and misunderstanding. True spiritual practice involves a deep, ongoing process of shedding external layers and persistent inquiry. There is a deep meaning about constant reminding in shastra about the necessity of humility, patience, and diligent practice on the spiritual path.

from ("Waking Up"):

Sam Harris: Poonja-ji’s influence on me was profound, especially because it came as a corrective to all the strenuous and unsatisfying efforts, I had been making in meditation up to that point. But the dangers inherent in his approach soon became obvious. The all-or-nothing quality of Poonjaji’s teaching obliged him to acknowledge the full enlightenment of any person who was grandiose or manic enough to claim it. Thus, I repeatedly witnessed fellow students declare their complete and undying freedom, all the while appearing quite ordinary—or worse. In certain cases, these people had clearly had some sort of breakthrough, but Poonja-ji’s insistence upon the finality of every legitimate insight led many of them to delude themselves about their spiritual attainments. Some left India and became gurus. From what I could tell, Poonja-ji gave everyone his blessing to spread his teachings in this way. He once suggested that I do it, and yet it was clear to me that I was not qualified to be anyone’s guru. Nearly twenty years have passed, and I’m still not. Of course, from Poonja-ji’s point of view, this is an illusion. And yet there simply is a difference between a person like myself, who is generally distracted by thought, and one who isn’t and cannot be. I don’t know where to place Poonja-ji on this continuum of wisdom, but he appeared to be a lot farther along than his students. Whether Poonja-ji was capable of seeing the difference between himself and other people, I do not know. But his insistence that no difference existed began to seem either dogmatic or delusional.

On one occasion, events conspired to perfectly illuminate the flaw in Poonja-ji’s teaching. A small group of experienced practitioners (among us several teachers of meditation) had organized a trip to India and Nepal to spend ten days with Poonja-ji in Lucknow, followed by ten days in Kathmandu, to receive teachings on the Tibetan Buddhist practice of Dzogchen. As it happened, during our time in Lucknow, a woman from Switzerland became “enlightened” in Poonja-ji’s presence. For the better part of a week, she was celebrated as something akin to the next Buddha. Poonja-ji repeatedly put her forward as evidence of how fully the truth could be realized without making any effort at all in meditation, and we had the pleasure of seeing this woman sit beside Poonja-ji on a raised platform expounding upon how blissful it now was in her corner of the universe. She was, in fact, radiantly happy, and it was by no means clear that Poonja-ji had made a mistake in recognizing her. She would say things like “There is nothing but consciousness, and there is no difference between it and reality itself.” Coming from such a nice, guileless person, there was little reason to doubt the profundity of her experience.

|

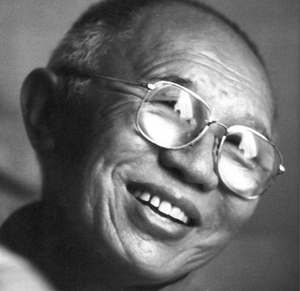

| Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche |

When it came time for our group to leave India for Nepal, this woman asked if she could join us. Because she was such good company, we encouraged her to come along. A few of us were also curious to see how her realization would appear in another context. And so it came to pass that a woman whose enlightenment had just been confirmed by one of the greatest living exponents of Advaita Vedanta was in the room when we received our first teachings from Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, who was generally thought to be one of the greatest living Dzogchen masters. Of all the Buddhist teachings, those of Dzogchen most closely resemble the teachings of Advaita. The two traditions seek to provoke the same insight into the nonduality of consciousness, but, generally speaking, only Dzogchen makes it absolutely clear that one must practice this insight to the point of stability and that one can do so without succumbing to the dualistic striving that haunts most other paths.

At a certain point in our discussions with Tulku Urgyen, our Swiss prodigy declared her boundless freedom in terms similar to those she had used to such great effect with Poonja-ji. After a few highly amusing exchanges, during which we watched Tulku Urgyen struggle to understand what our translator was telling him, he gave a short laugh and looked the woman over with renewed interest.

“How long has it been since you were last lost in thought?” he asked.

“I haven’t had any thoughts for over a week,” the woman replied.

Tulku Urgyen smiled.

“A week?”

“Yes.”

“No thoughts?”

“No, my mind is completely still. It’s just pure consciousness.”

“That’s very interesting. Okay, so this is what is going to happen now: We are all going to wait for you to have your next thought. There’s no hurry. We are all very patient people. We are just going to sit here and wait. Please tell us when you notice a thought arise in your mind.”

It is difficult to convey what a brilliant and subtle intervention this was. It may have been the most inspired moment of teaching I have ever witnessed. After a few moments, a look of doubt appeared on our friend’s face.

“Okay . . . Wait a minute . . . Oh . . . That could have been a thought there . . . Okay . . .”

Over the next thirty seconds, we watched this woman’s enlightenment completely unravel. It became clear that she had been merely thinking about how expansive her experience of consciousness had become—how it was perfectly free of thought, immaculate, just like space—without noticing that she was thinking incessantly. She had been telling herself the story of her enlightenment—and she had been getting away with it because she happened to be an extraordinarily happy person for whom everything was going very well for the time being.

This was the danger of nondual teachings of the sort that Poonja-ji was handing out to all comers. It was easy to delude oneself into thinking that one had achieved a permanent breakthrough, especially because he insisted that all breakthroughs must be permanent. What the Dzogchen teachings make clear, however, is that thinking about what is beyond thought is still thinking, and a glimpse of selflessness is generally only the beginning of a process that must reach fruition. Being able to stand perfectly free of the feeling of self is the start of one’s spiritual journey, not its end.

No comments:

Post a Comment